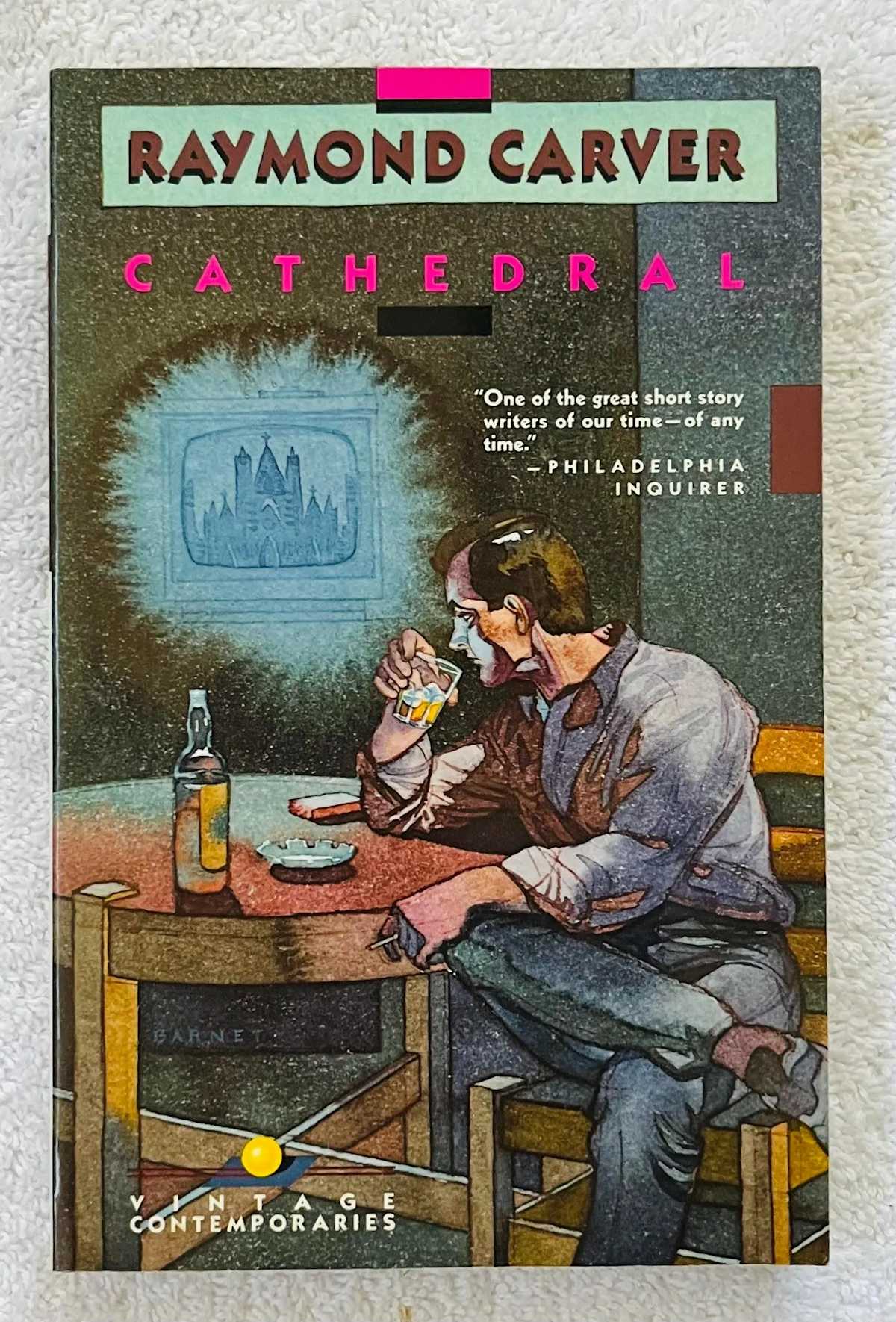

I’m not sure when I read Raymond Carver for the first time. I know he was he was still alive. I looked forward to new stories in Esquire and The New Yorker. Then he died of lung cancer. He was only fifty. I suspect he lived as his protagonists did—antsy, struggling, hoping for a break, smoking and drinking heavily, life never what they wanted.

I was twenty-seven when Carver died. By the time I turned thirty I had read all his stories, many two or three times. I tried reading Carver’s poetry but didn’t like it. I thought he was trying to do similar things in his poems as he was doing in the short stories. He was going for bare-bones descriptions. Sparse. Straightforward. Compact. The style can work in poetry. With Carver, though, it was a letdown because he was already doing it masterfully in his short stories. There was nothing special about his poetry.

Because of his style, Carver can be read as simple. From time to time, I’ve read him that way. It always left me wondering what the hell the story was about. For Carver, it’s usually about a variation of the themes of alienation and failure. His stories are populated by unhappy people trying to get by. They have dead-end jobs, lousy marriages or life-sucking divorces, annoying neighbors, and kids they tolerate, at best.

To read Carver as simple, though, is to ask, “So what?” By the end, you feel you wasted your time. Everything stops too soon, as if the last page were cut off. Protagonists are no different or further along than when they started. There’s no epiphany or change of plans or circumstances. It’s Carver’s way of saying, “Yep, it’s all true. Nothing changes.”

To read Carver deeply, however, is to know the hard lives he writes about are as true to form as most writers will get. That’s the magic of Raymond Carver. He lived a hard life and figured out a way to convey what that is like without one iota of sentimentality or explanation. He did it time and time again, with different protagonists, different contexts, somewhat different problems, similar outcomes.

It’s not that if you’ve read one Carver story, you’ve read them all. Far from it. The more of them I read the more I wanted to read. Sure there are similarities of theme, tone, and style, but the protagonists are too real and too submerged in their own problems to be confused with one another. You’ll find yourself saying repeatedly, “I know this guy” (and it’s usually a guy) not because you read about him or someone like him elsewhere before but because people like him exist. You know them. What you don’t know is what protagonists are going to do or not do over ten to fifteen pages to further screw up their lives. Each story is like an accident you can’t turn away from.

The simplicity of the writing—and I hate calling it simple but that’s what it feel like—can be both a detriment and elixir. It can cause you to miss much, or it can cleanse your soul of bad vibes and thoughts and keep you moving forward. On top of that, to those that aspire, the stories are tutorials on how to write, if writing like Carver is your thing.

I know no one who came after him who writes like him, although I suspect MFA programs were full of Carver wannabes in the early 1990s. Prior to Carver, Hemingway and Sherwood Anderson wrote in similar ways. Anderson created characters that look, sound, and live a lot like Carver’s or vice versa.

Smoking killed Carver in 1988. Lung cancer. I remember when I heard. I was trying to be a writer. I felt my life to be like Carver’s, without the smoking and drinking, or as not as much of the smoking and drinking. My life was like many of Carver’s protagonists. I wasn’t going anyplace personally or professional. I was living the themes. My only aspiration was to write like Carver. I couldn’t.

Then I read an article about how Gordon Lish, Carver’s editor, edited down and refined much of what he wrote. The article included a page of a story draft with Lish’s editing marks—a real mess of feedback. I was disappointed and angry. It was something one of Carver’s protagonists might do.

I stopped reading Carver (and stopped writing but not because of Carver)…until a few weeks ago. I pulled off the shelf a book of short stories and began to read them. I had begun to write short stories again a few weeks earlier. They’re about my travels during my youth and how messed up I was as a young man—a failure and alienated. I’m going to share some excerpts over the next few weeks.

Where thirty years ago I wanted to imitate Carver, I no longer feel the need. Hubris, though, keeps me believing Carver and I are similar, both in what we’ve experienced and in our writing. I know, in writing about him here, I’m trying to mimic him. A sign of respect, maybe? But I’m a different writer. I live a different life, more so now. I don’t smoke or drink even a little. I’m well past fifty. Those last few lines could be the start of a Carver story. I can’t help myself.